Hubspot: Growing via Culture

Hubspot (HUBS) produced a 150 slide document few companies bother with: A culture code. This is music to the ears of a human capital investor.

This essay is a sample of the Premium Newsletter that explores owner-operators and cultures of public companies.

Other free samples:

If you would like to read the full archive, consider signing up for the free trial here:

Hubspot (HUBS) produced a 150 slide document few companies bother with: A culture code. This is music to the ears of a human capital investor. The powerpoint puts HUBS in a rare group with others like Netflix and Activision Blizzard. Who are these leaders that would go out of their way to make hundreds of slides about culture? Even if it’s bullshit, it takes a lot of work and they’ve earned my attention.

My fascination begins with Brian Halligan (CEO) and Dharmesh Shah (CTO), the co-founders of HUBS. What does their company do? HUBS provides marketing software to mid-sized businesses. The engineers met as MBA students at MIT. Prior to MIT, Shah bootstrapped his first company and sold it for millions and Halligan worked as a sales executive for a tech company that got acquired by Microsoft.

Unlike most startup founders, Shah and Halligan started with money in the bank - fuck you money. They didn’t need a quick win out of HUBS when it launched in 2006. It allowed them to think long-term to build a company Halligan said: “their grandchildren would be proud of.”

It started from Shah seeing his personal blog grow without outbound marketing. Halligan was having the opposite problem as a venture capitalist. Money wasn’t solving the growth problem for his portfolio companies. Instead of replicating Shah’s blog strategy to consult, the duo decided to build a software stack they could rent out to companies struggling to grow.

Who’s Talking?

Any CEO can say they are thinking long-term. I haven’t heard any say they will maximize short-term gains and make a toxic company. Yet, most do. For their words to have merit, I need to see them put their money where their mouths are.

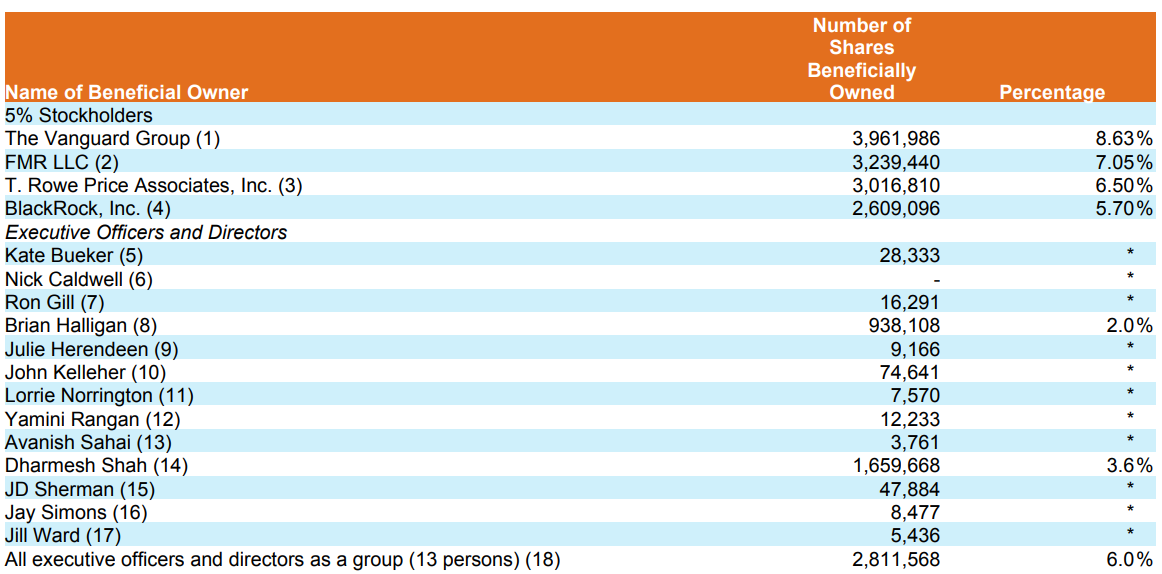

Halligan and Shah owned 5.6% of HUBS per the 2020 proxy statement. That’s ~$1.1b between the co-founders at HUBS’s Summer 2021 market cap of ~$23b. That's skin in the game. I can’t imagine leaders without most of their money tied to the business truly caring about it. I think money keeps the labour of love honest - no matter how passionate the entrepreneurs are.

The co-founders followed other tech entrepreneurs like Jobs, Zuckerburg and Dorsey by electing to pay themselves $1 in salary and forego annual bonuses. I applaud their resolve to fully tie themselves to HUBS’s equity. They, however, get paid $2m to $4m in options and RSUs that vest over four years. For guys worth $1b+ it’s not a lot of money to flag concerns of abusing equity. I see it comparable to the “other compensation” line many tech CEOs fill up for personal luxuries. I’m willing to trust what they say in regards to HUBS’s long-term future.

Humble, Empathetic, Adaptable, Remarkable and Transparent (HEART)

I first read HUBS’s culture code last Winter. Turns out, 5m+ have read it too. In my short write-up, I applauded their transparency, fostering individual mastery, forgoing people who want predictability and stability, and hiring those with HEART.

Halligan and Shah noted how exceptional culture is no longer a differentiating factor but table stakes to building a great company. I agree. There is no alternative when human capital is the engine for most companies.

I want to highlight a few concepts from my previous essay. The first is autonomy. HUBS has a three-word policy for most decisions: Use Good Judgment.

This puts the onus on the employee to be an adult. It makes thinking the default. A prerequisite to HUBS’s emphasis on refactoring, a process “to improve internal structure without changing external behaviour.”

I think their process of refactoring embodies the “less is more” philosophy. It’s how employees remove useless rules, reports, and meetings. It’s understanding that behaviour shifts when structure changes. One example is how employees can expense any meal where they take someone smart out to dinner. It incentivizes curiosity. Can someone abuse it? Sure, however, that’s the cost to developing top performers.

Halligan led by example by meeting with executive teams of Dropbox, Google and Atlassian to learn about the freemium model and building a strong culture. He even went on a world tour to interview CEOs of technology companies to feed his own curiosity.

He highlighted Yvon Chouinard of Patagonia and the Scott Farquhar and Michael Cannon-Brookes of Atlassian as leaders he admired. Both are companies I would put among the global elite in obsession over culture. Doubling down on his word, Halligan added Jay Simons, ex-president of Atlassian, onto HUBS’s board of directors.

Not only does Atlassian have an obsession with culture, they are a rare B2B software company without an enterprise sales team. It appears HUBS is taking another step to learn from Atlassian.

Shah and Halligan have also embraced the values of individual mastery through their annual 360 reviews. They perform the review for each other and Halligan noted Shah usually has 30 pages of notes for him.

One feedback Halligan took was to step down from his product leadership position earlier in the company’s growth. I think it’s an incredible sign of humility to see the founder and CEO admit he is not the best person for the product and hire someone more competent. It shows a leader able to be honest with himself. An honest organization needs honest leaders.

What Have They Built?

HUBS’s mission is "helping millions of organizations grow better”. HUBS proposes to achieve this through its customer relationship management (CRM) platform. It’s a suite of cloud-based software products that helps companies with marketing, sales, and customer service - everything on the front line. It sounds like selling knives in the knife fight of capitalism.

Subscription revenue accounted for 97% of 2020’s total revenue of $833m. They sell tiered plans with most payment plans lasting a year or less. It’s a typical recurring revenue model striving for higher annual recurring revenue (ARR).

Their Customers

Their customers are mid-market B2B companies - defined as 2 to 2,000 employees. Solutions partners - firms that use HUBS to serve their clients - accounted for 35% of total customers and 43% of the $833m HUBS earned in revenue for 2020. I’m reminded of all the digital marketing agencies that buy Facebook ads for customers.

Is HUBS building a layer of businesses that run on its own platform? By building a product that can scale with the growth of customers, they’ve made it easier for the solution partners to grow seamlessly as their customers grow as well. I’m not a developer, however, I think the platform’s use of open-source distributed technologies like Elastisearch, Kafka, and HBase will be favourable in managing the financial strain as the business grows.

With a one-stop platform, I can see how HUBS is trying to embed itself deeply into the work process of its customers. HUBS helps customers grow revenue. That keeps their customers in business. It’s quite the alignment of interest. The more HUBS’s software is integrated into the customer’s workflow, the harder it will be to pull out. Growth that builds layers of bureaucracy of workflow. Workflow that has HUBS as the foundation.

I would find it hard-pressed to see customers leave HUBS if it’s working. Customers leaving will mean they couldn’t grow revenue. Either way, it’s a win for HUBS. They only make money from growing customers. Without any customer accounting for more than 1% of revenue, the inevitable churn of customers should be a normal sign.

Is It Working?

Has focusing on culture helped HUBS? Halligan sees Salesforce and Microsoft as their main competitors in the CRM space. The former is estimated to have a 20% market share in 2018 with HUBS having 3.4%. It is, however, difficult to take that at face value with their market share in the marketing automation segment to be 29% in 2020 while Salesforce is at 4.9%. Either way, I think they’ve built something competitive that warrants a closer look - industry numbers should be held lightly in a field where the participants are constantly morphing.

Since 2017, revenue grew 30% annually with gross margins averaging 80% - optically standard for SaaS companies.

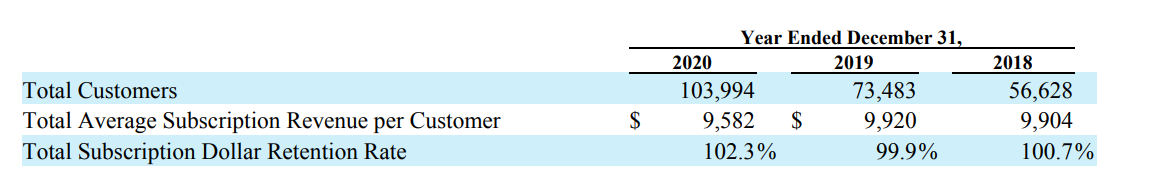

In regard to revenue growth in 2019, Halligan said 50% came from freemium conversion and 50% from content. Both are organic channels that build on the software platform doing its job and the library of content they’ve amassed over the years to help customers. They help customers generate inbound marketing and they appear to be championing it themselves. They’ve been able to grow customers at ~50% year over year on this strategy.

HUBS lowered the price for the starter plan in 2020 and noted the decrease in Total Average Subscription Revenue per Customer was the result of more customers buying the starter plan than existing customers upgrading to higher priced plans. I was surprised to learn the total customers do not include any free tier users. I saw this as another example of transparency and honesty - in a world where every software company inflates the truth with GMVs and free user growth.

The majority of HUBS’s operating costs were employment compensation allocated to R&D and Sales & Marketing. With growth coming organically, I see these costs as growth capital expenditure (CAPEX). Maintenance CAPEX would be the costs accounted for in the cost of revenue, PPE, and capitalization of software costs. This results in seeing an operating margin of ~40% for the business. That results in the owner earnings (OE) of the business coming out to nearly ~$400m.

With net cash of ~$500m the business appears to have the ammo needed to grow. They’ve built a product that appears aligned to the success of their customers. Their growth appears to be fuelled by a focus on product and content that requires creativity only a safe and autonomous environment can foster.

Competitive Dynamic

When I think about software businesses, I think most have an advantage once they get installed. In the beginning stage, I think the product has to speak for itself. If it’s a great product people will recommend it.

Halligan expressed their product needs to be 10% better, not 10x better than the competition. It’s a game of getting in early into a growing customer and scaling with them. This means being 10% better than the competitors in the early stages. A mark of a great product is one that doesn’t have to advertise - Atlassian comes to mind.

It appears that HUBS has a similar dynamic with the majority of customers signing up organically. It’s also the nature of the freemium model to have customers upgrade to be paying customers. Trust builds from using the product and the deliverance of result can’t be clearer than HUBS doing its job: increasing sales.

I don’t think HUBS is competing for the large enterprises that Oracle, Microsoft or Salesforce would go after. They’re looking for the small businesses they can hook into early.

I imagine HUBS is serving its purpose if growth increases as layers of bureaucracy builds. Growth declines as the customers get larger and when it comes time to rethink software needs, the customer is too fat. It has layers of processes and people trained on using HUBS. The costs to replace HUBS outweigh the benefits. Declining growth puts greater pressure on costs and it’s not a risk worth taking for middle management. I imagine HUBS'll lives with the customer until they die.

I think sales and marketing software will be stickier than engineer-focused software. Selling to engineers is considered a nightmare because many are skeptical and have high standards. My engineer friends are very willing to try new software products if they prove to be better. But they are also meticulous in examining its value. I imagine it’s because engineers know how the sausage is made.

Sales & Marketing people don’t have the knowledge engineers do. The product is there to serve them and as long as it does the job, they’ll keep it. I think it’s like accountants with ERPs. Once it’s in the workflow, it stays there for life. My guess is ERPs and marketing softwares will have higher switching costs than developer tools.

HUBS’s challenge exists in acquiring new customers. Every year new companies will come to take a slice of the 80% gross margin HUBS has. Every year new customers will ask themselves “Why Hubspot over xyz?” I think this is where the team Shah and Halligan built comes into play.

I think trust is what will continuously draw new customers to HUBS over others. This trust will require a constant focus on the customer. A focus that can’t exist if the employees aren’t invested in the business. That alone is a knife fight only the best teams can win.

Looking Ahead

This is not an exhaustive investment report on HUBS. It’s a starting point to see if the business warrants a place in my inventory of companies to follow. I admit the lack of shareholder letters makes me hesitate. The absence plays contrary to a company that seeks to be transparent.

HUBS currently trades at an enterprise value to sales multiple of 25x. Now, this is not a note on valuation. A company that grows 30%+ and has an 80% gross margin should look expensive. I’ve compared Atlassian to HUBS numerous times here and when Atlassian had ~$800m in sales in 2018, they had a ~24x multiple as well - they have 30x today. Optically, it doesn’t scream cheap to me.

I don’t know if HUBS is a great business. But I think it’s a good business. It makes a healthy margin and appears to be able to achieve this organically. I love how the founders view culture as the foundation of any successful company. I see what they’ve accomplished thus far as the result of a company that attracts and develops people to be their best.

I like that the founders have most of their net worth tied to the company’s success. The success of HUBS is directly tied to the top-line growth of its customers, an alignment in the business model itself. It’s one I’d like to continue to monitor and learn about.