#213: Shareholder Letters of Nick Sleep of Nomad Investment. Deep, Long Dive....

“Value creation is often most sustainable when it is built slowly…”

This essay is a sample of the Premium Newsletter that explores owner-operators and cultures of public companies.

Other free samples:

If you would like to read the full archive, consider signing up for the free trial here:

When I try to think about what attracts me to Nick Sleep, I think it’s as much him as an investor and the person I hear through his writing. When I first learned about him, I didn’t care to immediately inquire whether he had a great track record or not. It might be an indication of how I like to look at people first then the results second. I’ve been trained to go the other way around but I think nature prevails over nurture here and I’m rather inclined to stick with it.

I first heard about Sleep four years ago from a colleague who educated me on Zooplus, an online pet food company in Germany. I subsequently learned Sleep invested in Ocado, the British grocery deliverer, and Games Workshop, a tabletop game that took over a good part of my teenage years and most of my savings. He was also investing in Asos, an online retailer I was familiar with during my sneaker collecting days and I kept on liking him more and more as his investments seemed quite obscure for a “value investor”. Fair to say, I didn’t appreciate Amazon as a business at this point.

He continued to remain a mysterious character. Unlike Buffett’s interviews and letters, I could barely find anything on him. I had since given up on acquiring his letters but thanks to the internet and its constituents, I got a full set of Sleep’s Nomad Investment Partnership letters from 2001 to 2013. I mean c’mon! That’s an amazing name for a fund.

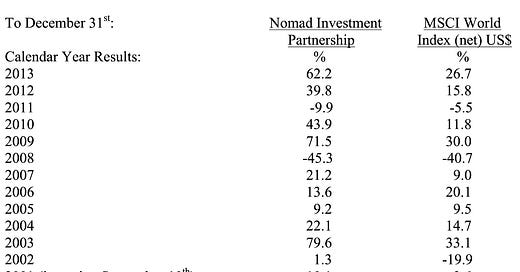

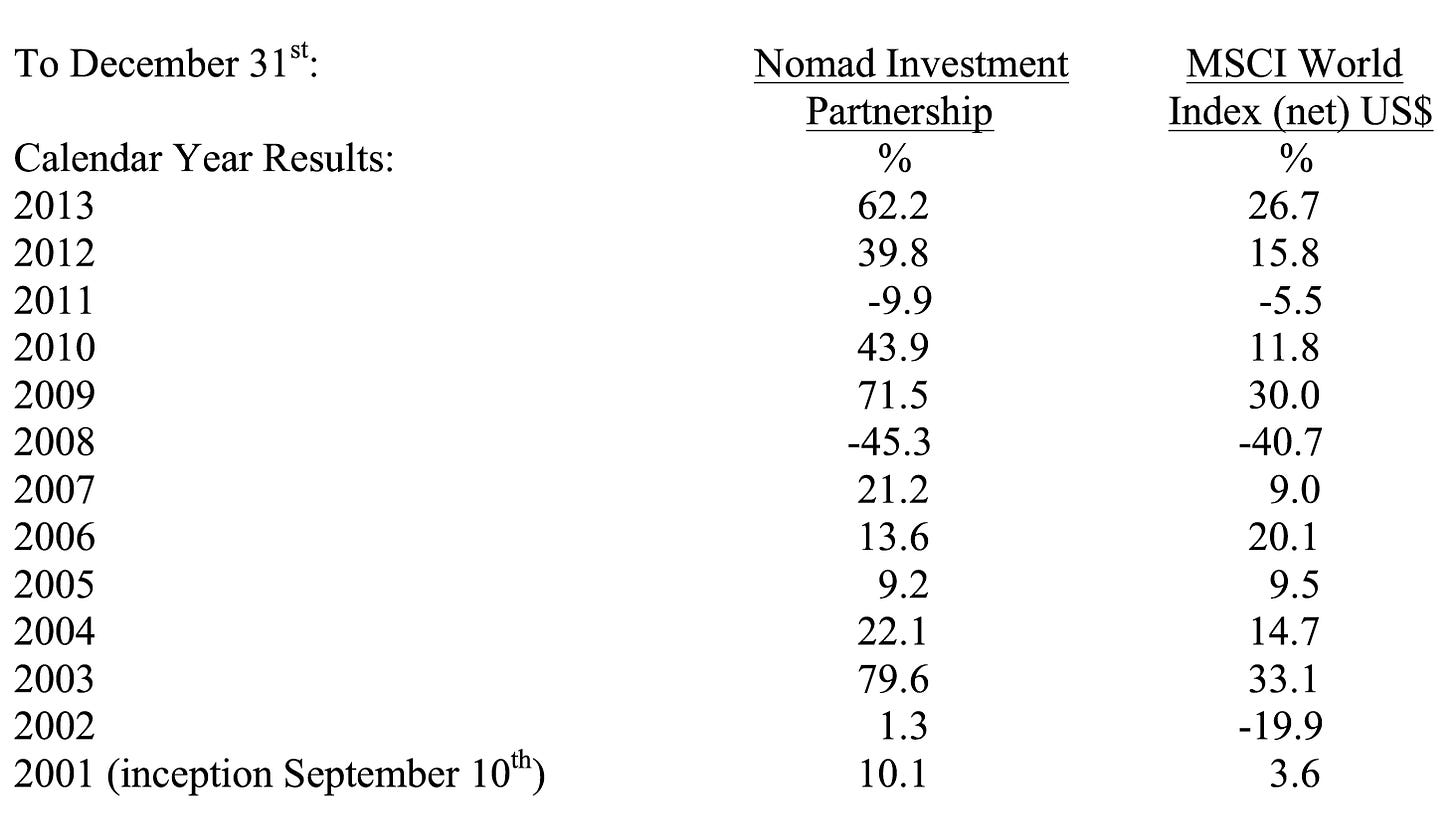

There were 25 letters over the 13-14 years of the fund’s existence. I think the fund stayed a low single-digit $bn fund where Sleep raised money at opportune times but since they were paid on performance past a hurdle rate (I think 6% like Buffett’s partnership letters), it wasn’t the typical asset-gathering fund. Over the life of the fund, he is annualized returns were ~20% before fees and ~18% net fees.

Sleep shut down the fund in 2014 as he told his investors that his recommendation was to merely hold Amazon (AMZN), Costco (COST), and Berkshire Hathaway (BRK) for the next 10 years. Regulations and strategy made sense to just give clients their money back with that simple recommendation. It hasn’t been 10 years yet but over the 7 years, AMZN returned 950% COST returned 282%, and BRK returned 115%. Not too shabby a recommendation.

Keeping with the tradition of the newsletter, I attempted to break out various learnings and thoughts into three categories of: Business & Investing, Culture, Systems & Work, and Introspection, Habits & Improving the Self. Now, some aren’t mutually exclusive so I recommend just dig through em all.

Business & Investing

Sleep’s Hammer & Nail: Scale Efficiencies Shared

Sleep’s interview with the Columbia Business School where he shares his analysis of COST is a must-read. Though, I imagine most people who are fans of Sleep would’ve already read it. Buffett and Munger have continuously touted the value of knowing one’s circle of competence and staying within it. It’s very much understanding what works in the world and tying it with what works for you as an individual. For Sleep, it seems to be businesses of certain characteristics. Many sharing what he believes to be a model called Scale Efficiencies Shared.

Throughout his letters, he shares analyses of businesses he has invested in. Some are: AMZN, BRK (i.e. GEICO), COST, Air Asia, Ocado, Zooplus. He also often mentions Ryanair, Southwest Airlines, and WMT. See similarities?

They all follow a business model that is low margin, cost-conscious, focused on scale, and sharing the benefits of the savings with their customers. A business model used to build the Ford empire in the 1900s, Walmart (WMT) in 70s, Southwest Airlines (LUV) in 90s and AMZN in 2000s.

This shouldn’t sound surprising but win-wins are good. A business doing well because its suppliers doing well and a business doing well because its customers doing well and a business doing well because its employees are well. A business should strive for all three and it makes sense that a business that does all three would be a good, if not great, business.

Such is the case for Costco. A business that pays employees more than any of its competitors. Gives them great benefits and more autonomy than any of the competitors. While most supermarkets make money by having suppliers outbid each other on price, Costco makes money by having suppliers outbid each other on how much value (savings) they give its customers. So suppliers don’t compete on price in Costco because Costco chooses to keep their gross margins fixed. They will only mark up by 15%. They are fine with that. They make money with increased purchases by customers because customers know they get the best value in Costco than its competitors. That’s how Costco is rewarded. They serve customers with the best value, they give their employees the best retail place to work, and they give their suppliers the best deal where it’s not the willingness to outbid on price but the willingness to outbid on value. Which makes their products and brands look better too.

Sleep considers such a model of scale efficiencies shared to be predictable for success.

Anatomy of Low Margin Businesses.

“Good things follow when you care about the pennies.”

Sleep points out a number of essential qualities that such great low-margin businesses have. One is an extremely cost-conscious culture. The kind of culture where the management team talks about fighting over pennies and making improvements by decimal percentage points. Such is the scale of these companies that a small percentage point improvement can have material impacts on the bottom line.

Another element seems to be vertical integration. The element of control Sleep continues to talk about with AMZN seems to be another core theme for other businesses that have scale efficiencies shared. Whether it’s COST owning all their stores to have a finger on costs, discount airlines owning one plane type to control parts and training, etc….

“The risk of super-normal profitability is that the profits are an incentive for a new competitor: far better, Zak argues, to earn less, but for a much longer time.”

Could you imagine a scenario where an already-dominant business continues to not raise prices but actually pushes prices further down? Highly effective low margin businesses are built that way by design and that can actually be their weapon. It further makes me wonder if low margin, low-cost businesses will actually face less competition. These businesses continue to build their scale advantage and it will cost a new entrant more and more in capital to get to a similar scale and investors may not be willing to fund such a low margin enterprise.

Local/Niche Dominance

In the early 2000s letters, Sleep shares how COST had penetrated ~65% of households in Seattle/Alaska and was moving down the West coast with under 10% penetration in other parts of the U.S. Now, one did not have to assume for exclusivity. People could still shop at COST and WMT as they aren’t mutually exclusive. One can argue the U.S. to be a more homogeneous environment than comparing to COST’s expansion into South Korea. You’d expect people to more likely have similar consumer habits in Ohio and Washington compared to South Korea. The U.S. is a big market and for COST in 2005 that was indeed the case. It was also very under-penetrated in most of this large market and with dominance in a few local areas, the combination of TAM and under penetration as a whole, was helpful to their growth. Especially where the service isn’t exclusive but rather, an additional option of value prop for consumers.

Much like how AMZN dominated books. Buying other goods is quite homogenous. Especially ones that fit under the category of “parcels”. So no AMZN won’t get all of eCommerce. They don’t need to. At least, they didn’t need to at the prices Sleep was purchasing the business at.

Reinvestments (Invisible versus visible)

In the 2010 letter, Sleep pointed out how AMZN’s investment in marketing was up 3x and infrastructure was up 4x while revenue went up 2.5x over a 3-year span. These are visible reinvestments. We can see the numbers on the financials (obviously, these too can’t be taken with absolute certainty but I digress). WMT and COST are similar operations that show reinvestment in their infrastructure as they primarily grow with each additional superstore while Amazon’s infrastructure is a mix of warehouses and data centres.

Some businesses are more one-dimensional in their reinvestment. Sleep uses Nike (NKE) and Coca-Cola (KO) as examples of businesses that funnel the savings on their scale to advertising. In ways, a reinvestment into taking up mindshare in consumer psychology. It’s what I consider the investment in “feeling”. To be associated with a brand, to feel something different from purchasing something they do not necessarily need.

The invisible reinvestment is in the money AMZN chose to forgo by giving back savings to customers. It’s the margin they didn’t take. Much like how COST caps their markup to 15% and all savings are passed onto the customers. AMZN continued to sell goods cheaper, provide the optionality, provide cheap shipping, etc… at much lower prices to customers. This only shows up as depressed revenue as some may wonder “what would their revenue look like if they wanted to price slightly higher?”

But this is the “flywheel” Jim Collins has frequently spoken about. AMZN/COST sells goods cheap, consumers like it and buy, they continue to find ways to sell at cheaper and faster and consumers buy more, etc… I think such tangible offerings like direct savings are much more sustainable than investing to take a hold of how consumers “feel”. A NKE/KO will have to convince consumers over and over again that they are worth the higher margin they are raking in while AMZN/COST don’t have to convince anyone since the low prices speak for themselves.

A dichotomy I see with consumer goods, particularly the discretionary luxury ones, is that if the business focused on quality…then growth might be non-existent. If the business truly produced a product that was so good that it didn’t have to be replaced for a long time (maybe a jacket you’ve worn for 10 years or a Kindle that lasts 7 years), continuous growth seems to be the antithesis. Yes, the business may grow slowly but if it’s to appease the rate of high growth a large-cap business needs to achieve to appease Wall Street, quality is not what these companies are necessarily selling. It’s, once again, a feeling from the association. I think consumers are smart and it’s not that they don’t know they’ve been brainwashed to feel something. I think they very well know that a sugary drink is bad for them and the additional pair of sneakers is unnecessary. But they do it because they just don’t care. I don’t see it being a sustainable thing to hope for consumers to continue not caring. However, I do think it’s sustainable to assume smart consumers will continue to make purchases at businesses that provide them with convenience and the best value.

I don’t see the marketing value of low prices on the financial statement. Instead, I see it as a negative with low revenue figures. The challenge is to look at the business to understand what the numbers show and don’t show.

The Evolving Story

“…the answer lies in analyzing not the effects and outputs of a business, but digging down to the underlying reality of the company, the engine of its success. That is, one must see an investment not as a static balance sheet but as an evolving, compounding machine.”

This may sound obvious but I must say I felt it rather profound when I read it. The financials are important but they are numbers that tell a story. The numbers themselves aren’t it. What are the numbers recording? Are we seeing a process that continues to execute and build-out?

Sustainable Growth

“Value creation is often most sustainable when it is built slowly…”

Is the business making hard choices now for an easy life later or easy choices now for a hard life later? How much of the upfront pain are they bringing forth? The default asks for faster and faster growth. If someone sees top-line growth of 30%, they expect 40% the year after. At the very least, the think 30% can be maintained for a long time. That’s ridiculously challenging. How many things are there in our personal lives that continue grow at high rates consistently? Very few. Much of the high growth in many companies comes from tradeoffs.

“….why grow if returns are going to be poor?”

A blind focus on growth appears the optically easy way out. Such is the case for aggregators who continue to pad revenue growth with acquisitions (many may not even be profitable). The bias is to think of such companies as the levered roll-up businesses because we’ve seen many blow up as they succumbed to their own weapon called debt. But debt was a proxy for cheap and available capital. This can be applied to ridiculous stock prices that are wielded as the same capital-as-a-weapon. It would be silly to not look at modern venture-backed businesses that continue to acquire other venture-backed businesses with equity with skepticism.

Using overstretched stock prices as a capitalistic tool is optimal for the company. But it’s also worth considering what such a financing practice says or doesn’t say about the management. Is it unnecessarily stretching itself beyond a level that it can’t sustain? Possibly. Ideally, you have an organization that only funds acquisition with cash. A business that prudently reinvests with the cash it has instead of stretching itself to be “optimal”.

Now, there are businesses where the entire model is dependent on rapid growth because that leads to higher market share and they need that volume to make the business work. They also need to grow rapidly because others are doing the same and each has VC cheerleaders who will throw buckets of cash on them to grow, grow and grow. So yes, it’s possible a focus on sustainable growth may not be applicable. But anything built with haste to reach a macro-state of equilibrium gives me pause.

Size

Sleep references Santa Fe Physicist Geoffrey West’s work on scale. West’s TED talk on “scale” is quite fascinating for the interested. West found that mass led to longevity (i.e. elephants live longer than mice). Mass also led to decreased heart rates. This led to a view that living creatures may have a set amount of heartbeats (around 1bn heartbeats in a lifetime apparently). Small animals had rapidly beating hearts and as they used up their quota relatively quickly, they died within a few years while larger animals could live longer. Now, I would think there is a diminishing return curve to size given how humans (i.e. small grandmas in Okinawa) might live longer than some whales. It seems the way bigger animals get around to having slower heart rates is having greater skeletal strength that allows for greater size, and greater size leads to circulatory efficiency and that leads to longevity.

Sleep further dug into what stops companies growing from a mouse to an elephant? In a sense, what limits its ability to scale? Sleep points out its complexity. Compared to a retail operation that starts from manufacturing to inventory warehouses to expensive real estate on Main Street with sales reps creating an experience, Amazon has a much simpler operation. A retailer has all kinds of complexity that may be out of its control. AMZN nailed this problem by controlling the website experience, breadth of products, the delivery experience, and anything they could vertically integrate.

Customers demand quality products, more options, helpful staff, a nice environment to shop in, and a host of other demands that a physical retailer will have to deal with. Not only through an e-commerce business model but also by trying to control as much of the process as possible, AMZN was able to be more consistent and probably contributed to its ability to scale more effectively. Is it as simple as viewing business operations that simplify the complexity by controlling the ecosystem will be able to scale more effectively?

Mo Money =/= Less Problems

“It can be tempting to think that more money is the answer to problems but it strikes us that it is not the money you have, but the choices you make, that count.”

In the 2011 letter, Sleep shared how he became involved with a troubled school in Southeast London as its governor through an independent foundation. Over the 4 year period, it went from a troubled school with an 85% exam failure rate to one with an 85% pass rate. The school didn’t receive additional funding. Rather, they overhauled the teaching staff to the kind of individuals who would be incentivized by helping students. They focused on spending money in areas that mattered to student development than on exterior toys.

Capital is one form of leverage. What’s important is a management’s ability to allocate capital effectively. Whether it’s in hiring great people, letting people build, scaling an experiment, or acquiring, having a lot on the balance sheet is useless devoid of a good allocator.

Robustness Ratio

It’s a measure Sleep shared in his 2005 letter. A framework he utilizes to see the width of a business’s moat.

Ratio = Customer value prop (i.e. how much customers save) / $ retained for shareholders.

An example would be how GEICO saved customer $1bn while earning $1bn. This would be a ratio of 1 as customers are expected to have saved as much as the earnings were retained for shareholders. Sleep estimated the ratio for COST was 5. The higher the ratio, the harder it is for competitors to compete.

“You can’t lose money shopping at Costco, but you can investing.”

An industry Sleep is frequently critical of is the investment industry. Particularly the kind of investment funds that run only on management fees or even more outrageously both high management fees and performance fees (i.e. 2/20). A few might justify the fees with amazing performance but most have what Sleep would call very low robustness ratios.

Costs. Not all bad.

Sleep breaks business down to the simplest form as cash in and cash out. No matter what other KPIs are, it must somehow translate to cash in and cash out.

Cash out are the expenses. Though the common dogma is to increase cash in and decrease cash out, Sleep breaks it down as a two-sided street. You want to eliminate bad costs. But you want more good costs. Good costs being money spent to invest in the right areas of the business. The parts that will let it compound.

There are also bad cash-ins as well. Good cash in is the cash flow generated from selling goods. But some will supplement with financing via debt and/or equity. That isn’t ideal.

Culture, Systems & Work

Decision Making

“Act in haste - repent at leisure."

It’s hard but worth it to train oneself to keep a cool head under pressure. But reminders aren’t good enough. Most times, I think staying away from the pressures helps keep the head cool so you can assess after the fact. It might be sub-optimal but most things aren’t so life-altering. Whenever a decision seems like it’s being forced upon you, it’s probably best to stop. To push it away. After all, most decisions shouldn’t be forced to be made so quick.

“Immediate gains are perceived positively compared to larger deferred gains as the limit (survival) system has the ability to over-ride the front-parietal (analytical) system. Interestingly, stress induces this override, and of course, money induces stress. So, the more stressed we are, the more we value short-term outcomes!”

Could the way to making effective decisions be rooted in creating an environment that limits stress? This would be effective to implement in one’s environment construction. It could be staying away from social media. I personally find staying from my newly recognized addiction of FinTwit until after 5 pm (when markets close) to be quite helpful.

Monetary stress, like an economic recession, might possibly lead to more individuals taking irrational amounts of risk in the hope of “quick money”. This might also help with thinking about how the market is driven by factors that contrary to how you view the world.

“There is no such thing as information overload, only filter failure” - Clay Shirky

Given most information has a sell-by date, like food. We would do well to focus our limited time on information with the longest shelf life instead of quarterly earnings or daily news. Most of what happens every day around us are irrelevant to our next month, year and life. It seems quite a fool’s errand to forecast a company’s behaviour based on news (i.e. acquisitions, new hires, competitor news). Without actually being inside the organization, it’s silly to think we can actually have such certainty in guessing.

Rules

“…often, if one removes the rules, and instead ask people to think for themselves, the system works better.”

A reference to the Santa Fe Institute study on “How individuals Learn to Take Turns: Emergence of Alternating Cooperation in a Congestion Game and the Prisoner’s Dilemma”. I quite believe trust is earned through one’s ability to demonstrate how one thinks. With that being said, many rules inhibit this very act of thinking, so a rule-based organization seems doomed to be one that will lack trust. This isn’t to say all rules are bad. Some are great to actually help one focus on the important things. But most rules in organizations are rather inhibiting of progress.

Invert.

If 33% of people want something, maybe the question shouldn’t be why they do but why do the 67% not want it?

Small Things.

The idea of not doing one big thing better than others….but doing many small things slightly better than others. Doing a number of small incremental things well. This, in essence, is a competitive advantage that a strong organizational culture breeds. A mindset to focus on each small development can only be incentivized from the top-down as employees need to be trained to think that is important. Most will default to bigger/better but it’s the leader’s job to stress the importance of the details and let the many small wins to compound over time.

A good reference is the 452 detailed goals AMZN shared in their 2010 annual letter. Not only is it about the detailed goals but it’s about setting goals that are within their locus of control.

Divine Discontent w/ Status Quo

Introspection, Habits & Improving the Self

What Works in Business + What Works For You

Investors would do well to study business history. Because that’s where they will hopefully learn what works! Then, of all the things that work, the next prudent thing is to figure out how that fits to who you are as an investor! Sleep figured out one model that works is one of low margins, low prices, and economics shared. And that made sense to him and he understood it and with his hammer, those were the nails he hit.

What is Investing?

“Pass custody (of your investment) over at the right price and to the right people.”

Where is Everybody?

“Highly priced shares are rarely illiquid.”

Competition is at the short end of the equity yield curve where financials are used to dictate short-term price movements. The long end has less competition.

Stoicism

Focus on what is in your control. Sleep refers to Stoicism in his 2007 letter and I couldn’t help myself from mentioning how awesome that is.

Wisdom Requires Focus

“The art of being wise is the art of knowing what to overlook.” - William James

Sleep shared a story with Sir David Attenborough in his 2012 letter. When asked whether he had indeed seen more of the world than anyone else, Attenborough redirected his answer to a different question in that Darwin only traveled for 4 years and spent the rest of his life thinking and his influence on our world was much greater than Attenborough’s had been.

Life isn’t merely about collecting all the data but to actually think with the information one has.

The Best Investors

Mohnish Pabrai, another investor I absolutely love learning from, previously quoted who Sleep considers to be the best investors:

“….the best investors were entrepreneurs who kept stock in their businesses”

It’s not just that these entrepreneurs didn’t sell early, but that they also made a big concentrated bet as most tend to have their entire net worth in their business. In his 2006 letter, Sleep noted how he should’ve made AMZN a 100% position. By 2006, AMZN was ~17% of the fund and it continued to grow to 30% by 2009.

Sleep noted how his mistake was to think of each new investment bottom-up in terms of allocation. He would start with 0% and move upwards. This made him susceptible to the anchoring bias to the starting 0% weight. Instead, he noted the inverse. To start with making the new investment 100% of the fund and moving down. After all, an element of investment success is to bet big when it is truly an amazing business.

“The trick, it seems to us, if one is to be a successful long-term investor, is to recognize the sources of enduring business success, get in early and own enough to make a difference.”

The two things in your control are to buy (preferably earlier than the masses) and buy big.

Variant Perception

Investing isn’t always about having the most contrarian opinion. Even a slightly different view can account for everything. Especially if the time horizon is much greater and it lets you bet big for a long time.

Although Sleep didn’t explicitly attribute “slightly different view” to AMZN, he dug into how growth rates for a large e-commerce company might not falter towards the “reversion to the mean” scenario that is common with base rates. Especially in such a scenario where the industry itself is still very young. Base rates of past companies may not have any idea what an e-commerce company built on the internet could actually do…because we didn’t have that before.

It’s a view of asking: “what if the limiting factor to the growth is not saturation of customers but a psychological attitude?” Where the attitude of buying things online will need to shift for people to embrace it further, rather than concluding that people will only spend a small % of their total spendings online and that being final. It’s quite admirable that he had such an insight when he bought AMZN in… I think 2006?… and continued to learn to share more insights in every letter.